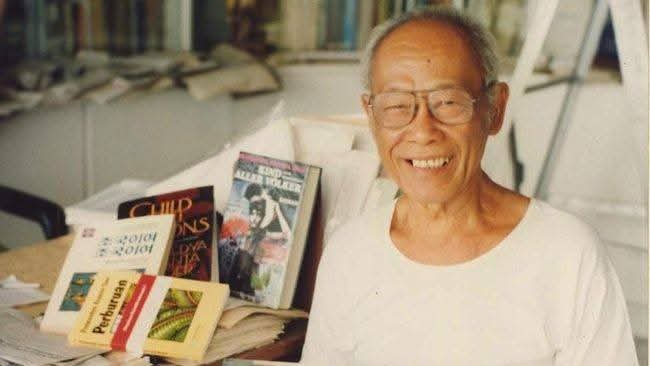

100th Anniversary of Pramoedya Ananta Toer: Amnesty Calls for Freedom of Expression and Release of All Prisoners of Conscience

“The newsletter featured Pram’s profile as a prisoner of conscience, alongside others imprisoned merely for peacefully expressing their views,” said Usman.

The newsletter detailed the cases of Pram and other prisoners of conscience from countries including South Africa, Spain, Taiwan, Cuba, Tanzania, the Czech Republic, Paraguay, Namibia, Turkey, and Hungary.

In 1972, Amnesty sent a letter to its global movement members, making Pram’s case a focal point of their campaign. The organization mobilized hundreds of thousands of its members around the world to pressure the Indonesian government to free Pramoedya. He was eventually released in 1979.

During his detention on Buru Island, Pram even faced the risk of being executed without trial. A fellow political prisoner informed Pram’s family about the imminent threat, prompting them to contact Amnesty International. Thanks to the intervention, Pram survived the extrajudicial execution attempt.

In a media interview, Pram’s daughter, Astuti Ananta Toer, shared how Basuki Effendy, a fellow political prisoner, warned her that her father was at risk of being killed and urged her to contact Amnesty International immediately.

Beyond imprisonment, Pram was also forbidden to write while on Buru Island, at least until 1973. Access to pens, pencils, and paper was denied. Amnesty International sent a typewriter to Pram on the island so he could continue his work.

“Amnesty learned that the first typewriter, which had been sent by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, broke down. Consequently, Amnesty sent a replacement, which was delivered to Pram through an International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) officer,” Usman explained.

Tinggalkan Balasan